The impact of implementing a reflective practice approach in the design of in school tasks.

Jayne Carter has been looking at the ways she delivers professional development and looks at a reflective practice approach.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development (n,d)) present reflective practice as “ …the foundation of professional development; it makes meaning from experience and transforms insights into practical strategies for personal growth and organisational impact.” (p2)

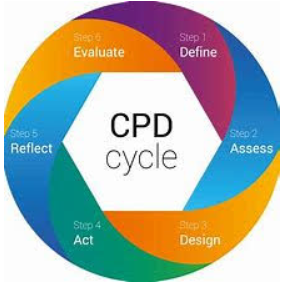

A reflective practice approach, in my opinion, offers much more than simply being a deep thinker, whereby an individual considers their personalised view regarding a specific area; being reflective. The practice aspect is the development of the skill of using this reflection base as a tool for personal & professional change which continues beyond the PD session. To adopt a reflective practice approach, in my experience, means that an individual is open to critical thinking at a high level, both professionally & often personally & is accepting to use their documentation of changes in their thinking as way of evoking sustained improvements in their subject knowledge & pedagogy.

It is this aspect that, as a PD lead, I wanted to explore more in my intention to design, implement & evaluate professional development which shapes knowledge & implementation alongside the acquisition & development of academic life skills for participants.

In the design of this project, my planning for the in school tasks followed these lines of enquiry:

The purpose of the in school task: why am I asking practitioners to engage in this specific task? What is the purpose of this task & how does it compliment the aims & outcomes of the whole project? Is it to reflect on a piece of research for personal conclusions or consider key findings this research highlights based on children’s involvement in learning? Is it to challenge practitioners thinking & if so, how does this specific task provide the necessary tools for this movement into new possibilities? Does its purpose provide opportunities for participants to develop their own analytical skills; providing much more than a process based task? Does it offer the opportunity for participants to hone academic skills & attitudes which furthers their professional development throughout this project & beyond? Is there potential for this in school task to provide an impetus & framework for discussion with other staff in school & contribute to whole school decisions? Integral to my reflections on this planning stage of the project were the findings included in the publication by the National College of School Leadership (2012) who offer an overview of the research debating what constitutes effective PD, based on its impact on participants & children. The need to dedicate thought to the intention of any PD experience, even at the planning stage, is highlighted continuously throughout this document, with its significance being attributed to the success in its subsequent delivery & completion.

“Successful professional development alliances draw together three principles: collaboration between schools, collaboration across time and collaboration with external partners” (p5)

Thinking ahead to the potential of the in school tasks crystallises the intention & propels my further planning into an impact based enquiry model.

The consideration of the design of the in school task: how would it be structured? What are the choices for this design over an alternative, considering the impact of any design in supporting participants? Do all participants need to complete it in the same way using the same outline, which is repeated in each session, so there is a consistency of approach during feedback & evaluation or could there be an element of independence within the broad parameter of the task, allowing for personal focus & preference? What would be the impact of these decisions in my role as PD lead; responsible for enhancing professional development? I am reminded of the significance of the research by the Teacher Development Trust (2015) which highlights the importance of preparing the design of any PD task with a focus on its applicability & credibility for deep thought & learning.

“The review tells us it is important that professional development programmes create a “rhythm” of follow-up, consolidation and support activities. This process reinforces key messages sufficiently to have an impact on practice.” (p13)

As a result of this, the structure of the in school tasks followed a sequential pattern with each section clearly acknowledged & respected for its potential in shifting thinking; creating the rhythmic pattern TDT advocate. The impact of this decision enabled me as PD lead to articulate the purpose of the in school tasks; drawing frequent connections to their role in scaffolding, challenging & supporting cognitive progress.

The explanation of the in school task: how much time should be dedicated within the PD session to discuss & explore the task? What is the specific language I should use to explicitly show the connection between this task & the main session? How would I address any misconceptions/concerns from participants & ensure clarity for all? McNiff (2002) offers this opinion of the role of a PD lead ‘Rather than a trainer, what is required in this process is a supporter — someone who will listen to ideas, perhaps even challenge them, and will help in identifying possible solutions.’ She continues to outline that the supporter should also be continuously learning with the participants; collaborating in a shared learning experience. I could sense this shift myself throughout the project in the amount of explanation I gave regarding the in school tasks designed. Initially, I did feel my approach was more didactic than collaborative, which was not entirely agreeable or intended. Inviting more opportunities for practitioners to summarise each element of the task & contributing their own plans moved this discussion into one which helped to raise the significance of the task within the project expectations & demonstrated valuing contributions from all.

How to structure the feedback for maximum impact: Isaac (1999) in his ‘model of dialogue’ offers considerations for supporting participants in any feedback activity, advocating for a ‘space for reflection. The model of dialogue provides participants within a conversation tool to ensure involvement from all, expecting respectful challenge & promoting alliance. This approach feels comfortable to me, as it acknowledges the needs of all & offers a nurturing discussion which focuses on a shared aim; learning. Being involved in the group discussions myself gave me a valuable opportunity to model the expectations & flow of reflections & conversations, as well as building up professional observations of specific practitioner needs which could then be included in future session planning. Varying the professional discussion groups (mixed provision type, mixed EYFS experience, size of group) not only enabled participants to collaborate more widely (thus sharing wider viewpoints) but also ensured that conversations were focused & channelled towards professional improvement. Focused questions & active listening, as included in Isaac’s model, formed the basis of conversations & conclusions which subsequently structured evaluations & analysis, providing valuable next steps for both facilitator & practitioner.

How to document observation & ideas: Schon (1984) promotes the value of representation as a powerful tool for defining thinking & prioritising cognitive changes; including this process in his reframing category of ‘reflection in action’ outlining:

“In reflection-in-action, doing and thinking are complementary. Doing extends thinking in the tests, moves, and probes of experimental action, and reflection feeds on doing and its results. Each feeds the other, and each sets boundaries for the other” (Schön, 1983, p. 280).

Whilst I appreciate the value of this as a vehicle in maintaining high levels of reflection & professional pondering, I also believe that it is vital to evaluate the most appropriate form of representation to truly make documentation meaningful & relevant to the individual. As we recognise the role of representation for children, the strength & potential of each style of representation in scaffolding learning for the learner & the viability of future secure recall & retrieval is paramount to its inclusion in the task. I therefore encouraged practitioners to document their thinking process (including outcomes & modifications) using forms such as mind maps, learning journey mapping, process lists or reflective diaries. This opportunity to be more flexible provided valuable & precious depth of conversations between professionals as well as first hand examples of new & innovative methods of journaling progress. This decision, I believe, helped me to move practitioners towards what Schon described as

“doing extends thinking in the tests, moves, and probes of experimental action, and reflection feeds on doing and its results. Each feeds the other, and each sets boundaries for the other” (Schön, 1983, p. 280)

an increased emphasis on the emotional changes involved in action research: included in Gibb’s reflective cycle (2013) is the aspect ‘feelings’ which acknowledges the emotional changes which can occur as a result of being involved in action research. This emotional connection I find personally useful in acknowledging the disturbance that you can feel as you move through the process of discovery & new learning. It is this memory which enables me to allocate an impact based summary of the experience I have been involved in; producing a more secure comprehension & storage of the learning content & experience. It is this aspect from Gibb’s cycle which I want to give more relevance to in the design, implementation & evaluation of the tasks. Learning isn’t a simple content processed activity; it connects with us at various different level; with the emotional sensation, despite its importance in the process being recognised & experienced, is often superseded by the level or amount of content achieved as a barometer of success. Paradoxically, as this project is focused on both the maths subject knowledge & the metacognition strategies, it was essential that both of these were mirrored in the PD delivery as without this union, my own authenticity to facilitation could be questioned. I ensured that this aspect of Gibbs reflective cycle was discussed just as often ( maybe even more so at the beginning of the project) as the corresponding aspects of the in school task ( observation, changes, evaluation) to provide not only a model of this for practitioners but also to help them draw on this element within their own learning trajectory. I also found it useful to structure this element of the process & direct practitioners towards firstly recognising how they felt during the in school task (particularly the application of new learning with children) & complement these feelings with suggestions which identified solutions; further building on critical reflection.

My deeper engagement with the in school tasks proved to be beneficial for the participants (outcomes stated that participants evaluated a high level of improvement, identifying the action research tool as effective both professionally & personally) but also positively affected my knowledge, confidence & cognition of the authenticity of this professional development tool. I continue to strive to achieve what Easton presents in this view;

“It is clearer today than ever that educators need to learn, and that’s why ‘professional learning’ has replaced ‘professional development’. Developing is not enough. Educators must be knowledgeable and wise. They must know enough in order to change. They must change in order to get different results. They must become learners.” Easton (2008 p756)