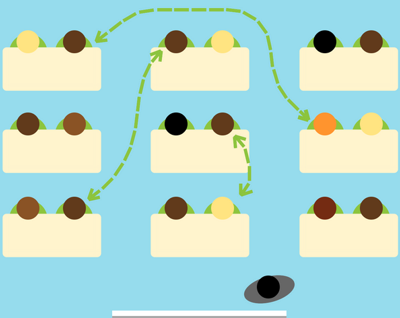

Our team sorts through all blog submissions to place them in the categories they fit the most - meaning it's never been simpler to gain advice and new knowledge for topics most important for you. This is why we have created this straight-forward guide to help you navigate our system.

And there you have it! Now your collection of blogs are catered to your chosen topics and are ready for you to explore. Plus, if you frequently return to the same categories you can bookmark your current URL and we will save your choices on return. Happy Reading!

Dr Poppy Gibson and Dr Robert Morgan

Recent strikes across all tiers of education have caused many to question why educators are not happy. If the average yearly fee is approximately £9,250 for 3 years, and £11,000 for accelerated per student (although this varies according to institution and area), where does that money go? Fees are even higher for foreign students on a postgraduate masters course. This short opinion piece from two academics ponders on where the university fees really go, and where they may be better spent.

Anecdotally, we have noticed a shift post-COVID19 where more students seem to be continuing to live at home with their families and choosing a local Higher Education (HE) provider. So what are students expecting from ‘getting a degree’? Is it just about earning a certificate at the end of the period of study, or should tuition fees offer something bigger and longer lasting? As we see a societal shift to greater understanding and awareness of mental health and wellbeing, the authors of this piece have also seen running parallel to this, a demand from students for more appointments to discuss anxiety and motivation, as opposed to the academic content of their course. Does this imply that students expect mental support as well as just their classroom learning, and if so, are tuition fees supporting this shift to greater pastoral care?

How are fees spent?

Research by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) revealed exactly where students’ tuition fees get spent, revealing that less than half of the money actually goes into the cost of teaching (Skoulding, 2022). In 2018, around 45% of the funds generated from each student’s £9,250 annual fees in England were spent on the cost of teaching, the remaining funds were spent on other necessary expenses. This includes things like buildings, technology and libraries, university administration, welfare support such as mental health services, and spending on the students’ union (Skoulding, 2022). According to the 2018 HEPI report, around 20% of tuition fees were spent on management staff, recruitment of students, advertising, and community work. The remaining money collected was spent on a range of other services, including administration and infrastructure costs.

Fees in a Marketisation of Higher Education

McGettigan (2013) analyses the current situation by placing modern university funding, including tuition fees, as a true market. Whether the marketplace is right for a democratic education place or not is one discussion, or indeed whether it is a true market for the fee-paying consumer, one aspect of marketisation is that the student should feel that the fees paid represent value for money. Students see the purchase of a degree, i.e. a transaction, but is there other consumer care that is required? This question is at the heart of the article.

The future of fees?

In our post-pandemic world, behaviours and expectations of education are changing. The surge of Artificial Intelligence in our classrooms is impacting how we create content, and how students interact with their learning. More and more courses are being offered as distance learning courses, and the future of HE is somewhat uncertain. The bigger societal picture here in the UK is one of the cost of living crisis and the brink of a recession. Should fees be lowered to make university more accessible to all? University chiefs argue that lowering fees would in fact be detrimental to those who are suffering financially, as reduced fees would probably equal reduced support in terms of bursaries and other financial help (Skoulding, 2022).

References

McGettigan, A. (2013) The great university gamble. London: Pluto Press.

Skoulding, L. (2022) This is what your tuition fees actually get spent on – Save the Student. [Online] Available at This is what your tuition fees actually get spent on – Save the Student

Dr Robert Morgan: Dr Robert Morgan is a senior lecturer in primary education at the University of Greenwich.

The author

Read more

Read more

Read more

Read more

Read more

Read more

Read more

Read more

Are you looking for solutions? Let us help fund them! Nexus Education is a community of over 11,000 schools that come together to share best practise, ideas and CPD via online channels and free to attend events. Nexus also offers funding to all school groups in the UK via nexus-education.com

Established in 2011, One Education is a company at the heart of the education world, supporting over 600 schools and academies. Our unique appeal as a provider is in the breadth and synergy of the services we offer, supporting school leaders, teachers and support staff to achieve the best possible outcomes for their pupils and staff.

School Space is a social enterprise that has empowered schools for over 12 years through their profitable and hassle-free lettings services. So far, they’ve generated over £5 million in revenue for education, helping to connect over 200 schools with their local communities.

Unify is an online sales and marketing tool that allows users to create tailored personalised documents in moments.

There’s nothing special about the energy we sell. In fact, it’s exactly the same energy as all our competitors provide. But there is something special about the way we do it. Where others complicate the process, we simplify it. Where others confuse customers with hidden terms, we’re an open book. And where others do all they can to make as much money from their customers as possible, we do all we can to make as little. Everything we do, we do it differently. Our customers are a privilege. One we’ll never take advantage of.

Securus provide market-leading monitoring solutions to safeguard students on ALL devices both online and offline. We also offer a full monitoring service, where we carry out the monitoring on behalf of the school, freeing up valuable staff resources. From the smallest school to large MAT groups, Securus offers safeguarding protection for all!

Bodet Time offers dedicated solutions to education through lockdown alerts, class change systems, PA and synchronised clock systems. Improving time efficiency of the working and school day; ensuring safety through lockdown alerts; increasing communication with customised broadcast alerts.

Robotical makes Marty the Robot - a walking, dancing coding robot that makes programming fun and engaging for learners as young as 5. Our robots come with a full Learning Platform that has complete teaching resources, to make lesson planning a breeze.