How often do people actually use what they learn from school out in the real world?

Georgina Torbet from Universal Owl writes about how schedules, learning environments and our body language already tell students an abundance without us even having to say anything.

This can have a positive or a negative effect.

If you feel like memorising dates of the French Revolution or the atomic number for argon is never going to be of any practical use, trust your intuition. You’re not wrong, and you’re not alone. In one survey only 48% of secondary students believed what they learned in class would help them outside of school. In an age when you can look up any fact on the internet within seconds, memorising textbooks is essentially pointless.

So, what do you really learn in school? Most students’ biggest takeaways are subconscious lessons like obedience, an achievement-oriented mindset, and a fear of failure. As you might have guessed, these translate to real life just as poorly as memorising useless facts.

Environmental cues subconsciously shape how we behave. If someone is part of a supportive and positive community and has the freedom to act as they want, they tend to behave in a more sociable, helpful way. Conversely, if someone is kept in a restrictive environment where they feel distrust toward the people around them, they’ll behave in a more selfish and destructive way.

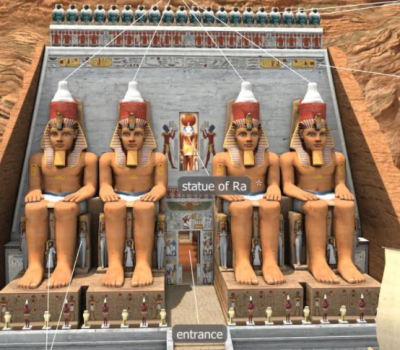

You would think that schools would be designed around principles that promote a positive and helpful learning atmosphere. Instead, schools have more in common with army barracks and prisons. Students are told where to go, when they may speak, how they must spend their time, and sometimes what to wear or how to present themselves. They should sit quietly and do as they are told and only question authority in certain situations.

These lessons are rarely spoken out loud, but students learn them all the same. If they speak out too much or if they don’t do as they’re told, they get in trouble. If they follow the rules, though, they get good grades and good reports. Those lessons stick even after their school career is over — which makes them all the more important to talk about.

With all these subconscious environmental cues in the classroom, what are students actually learning while in school?

Students are obliged to follow the instructions of teachers in terms of what they study, how they learn, and most importantly, how they behave. Prefer to study a practical subject like car mechanics instead of an academic subject like geography? Too bad. The school sets the rules and the students must follow them.

In recent years, education researchers have started to understand that people learn in different ways. Some students learn best from discussing concepts in a group, while others prefer visual information or a hands-on approach. It isn’t clear to what extent favouring or avoiding these styles has on a student’s ability to learn in the classroom. We do know that ignoring them creates long-lasting problems. Two thirds of post-education adults echoed this sentiment in a survey, stating that a focus on practical knowledge and improving individual skills is more valuable than standardised curriculums and teaching methods.

People are frustrated that school isn’t teaching them what they need. Instead, they walk away carrying damaging subconscious lessons like obedience. One thing is abundantly clear: sitting passively in a chair and copying information a teacher writes on the board is not the best way to teach everyone. It’s good for instilling obedience, but not necessarily for morale or passing along knowledge

Students are told when and where their lessons are and must attend them on time. They have practically no opportunity to design their own schedule.

Following someone else’s arbitrary schedule causes a variety of problems. One of the most prevalent is chronic sleep deprivation. Studies show that teenagers need more sleep than adults — around 9 to 9.5 hours compared to 8 hours for adults. Schools with early start times make getting enough sleep almost impossible. When students are tired it’s harder for them to concentrate, harder to retain information, and their overall mood is worse.

Thinking longer-term, it’s troubling that students never learn the skill of setting their own schedule. When students go to university or enter the working world, they’ll often have to decide for themselves how best to use their time. Juggling commitments like work, maintaining a home, family, friends, and hobbies is one of the biggest challenges adults face. With the existing school system students never have an opportunity to practice this skill.

Before a young person learns to balance competing demands on their time, it’s common to fail to achieve this balance several times. By prescribing how students should spend every minute of their time, we are robbing them of the satisfaction of forming good scheduling habits — to say nothing of the learning that comes from bad habits.

Students today face a never-ending stream of tests, assessments, and exams. Many are scared of failure and feel shame if they do not do well academically. This stems from what is called an achievement mindset — the idea that your worth is based on ticking off a series of achievements, like getting good grades, winning prizes, and getting into a good university. If you don’t accomplish these things, the achievement mindset says you are a failure.

Regardless of what your teachers and professors say, that’s an extremely unhealthy way to see life. Failure is not only inevitable — there is literally no one alive who hasn’t failed at something — it’s also an important learning tool, perhaps the most valuable one there is. Whether it’s in business, family life, or picking up a new hobby, trying and failing is how you gain experience and grow as a person.

Failure is a key part of a life well-led. If students are afraid to fail, they won’t push themselves to try new things. They’ll only stick with the familiar things they know they can do well. This achievement mindset is a recipe for an unhappy, unfulfilled life.

All of the above issues have a similar root: students lack agency over their learning. They aren’t allowed to decide what they want to study, how to arrange their time, or which learning styles suit them best. They are taught to follow orders and not to question what they are told.

As a society, we generally agree that people shouldn’t be forced into situations against their will. In many schools, however, if a student wants to do something as simple as use the bathroom they have to ask permission. This is highly infantilising and disrespectful of students’ needs as individuals. Adults report restrictions on autonomy are one of their greatest sources of dissatisfaction. Why would that be any different for young adults or teenagers?

An essential skill for adult life is learning to create and negotiate boundaries. What kinds of treatment are acceptable to you? How can you assert your needs politely but firmly? How do you balance your needs with the needs of others if they are in conflict? There is arguably no more important skill to develop for a satisfying, compassionate life. And yet, as schools currently exist, they undermine these very principles to force students into a one-size-fits-all model.

The next time you find yourself wondering what the point of school is — whether you’ll ever need the information you’re being taught in class — know that you’re right to be sceptical. The lessons school is teaching you just might be the opposite of the lessons you need to live a fulfilled life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Sp what mindset does your school impose?