Abstract

Trauma can be defined as ‘the sudden, uncontrollable disruption of affiliative bonds’ (Lindemann, 1944: 144). Trauma experienced in childhood can have the most adverse consequences when cognitive functions and the central nervous system are still developing and maturing (Van der Kolk, 2003). This article brings together an analysis of the literature to provide a detailed understanding of how trauma can affect children as well as explore practical ways in which social workers, carer givers and educators can aim to reduce trauma, and to support children who have suffered trauma. This article presents the ‘3-E’ trauma process model (NCSSLE, 2021) and then explores this model alongside trauma support. It is important for childhood trauma to be addressed early in order to reduce the possible effects of latent vulnerability, which is the link between trauma suffered in childhood and mental health problems later in life (Gerin et al. 2019). The education system can provide an integral role in addressing the effects of traumatic stress students experience through providing prevention techniques, early intervention and intensive treatment for children who have been exposed to trauma (Kataoka et al. 2018). This article links trauma theory to practice, and acts as an informative resource for social workers, care givers and educators.

Introduction

Trauma can be defined as ‘the sudden, uncontrollable disruption of affiliative bonds’ (Lindemann, 1944: 144). More recently, the UK Trauma Council describes trauma as ‘a distressing event or events that are so extreme or intense that they overwhelm a person’s ability to cope, resulting in lasting negative impact’ (UK Trauma Council, 2020:1). Trauma experienced in childhood can have the most adverse consequences when cognitive functions and central nervous system are still developing and maturing (Van der Kolk, 2003); childhood trauma can affect all areas of a child’s development, from their attachment and relationships with others, emotional responses, cognition and learning, physical health and daily behaviours. The ability to develop trauma informed practices within schools is an important topic. Teachers and those working in schools, are uniquely qualified to target childhood trauma prior to long term effects developing (Pataky, M. et al. 2019). This article will provide a detailed understanding of how trauma can affect children as well as explore practical ways in which educators can support children who have suffered trauma. It is important for childhood trauma to be addressed early in order to reduce the possible effects of latent vulnerability, which is the link between trauma suffered in childhood and mental health problems later in life (Gerin, M. et al. 2019). The education system can provide an integral role in addressing the effects of traumatic stress students experience through providing prevention techniques, early intervention and intensive treatment for children who have been exposed to trauma (Kataoka, S. et al. 2018).

Trauma can affect a child’s ability to regulate their emotions, behaviour and attention, this, in turn, can result in children appearing withdrawn, aggressive or inattentive (Cole, et al. 2005). Childhood trauma affects a child’s brain whilst they are going through a crucial developmental period, it can put a child in ‘survival mode’. This survival mode puts the child in a constant state of anxiety and readiness to deal with any possible threats, this impacts the prefrontal cortex of the brain and prevents the child from being able to think about or focus on anything else (Nealy-Oprah and Scruggs-Hussein, 2020). Hughes (2016:3) adds that as well as disrupted function to emotional and cognitive behaviours, trauma can result in children feeling ‘emotionally numb, cognitively confused, and very avoidant of many situations’.

What is trauma? The 3-E Model

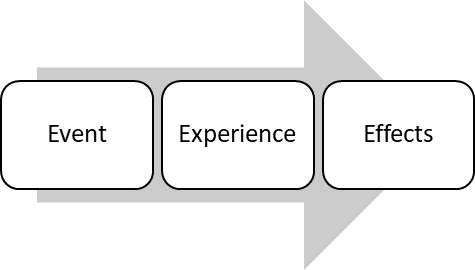

To help understand how trauma is caused in the body, it can be helpful to use the 3-E model (see Figure 1 below):

Using this model, trauma ‘is used to describe an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening, overwhelms our ability to cope, and has lasting adverse effects on a person’s mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being’ (NCSSLE, 2021:1). In the section below, the three ‘E’s of Figure 1 are expanded to help illustrate to the reader how trauma may be caused.

Events

Experiencing feelings of anxiousness is a normal human emotion. Anxiety refers to a state of excessive worry, a state of worry being experienced by an individual, despite no immediate threat being present, or at levels of worry that may be regarded as being disproportionate to the identified risk (Glasofer, 2021). Trauma is more than this, being caused through events that can either be a one-time incident, an accident, a natural disaster, loss of someone in the family or friend network, or a one-off violent experience (((SAMHSA). (2014); National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.)). Events can also be periods of abuse, neglect, bullying, exposure to violence, or even events fostered in long-term poverty, racism, or discrimination (NCSSLE, 2021).

Experience

An individual’s subjective experience of the event defines whether or not the event will prove traumatic. The subjectivity comes from a range of variables including a person’s coping strategies, the external social network that can support the individual post-event, as well as the societal and cultural beliefs and structures that influence how we regard and respond to experiences (NCSSLE, 2021)

Effects

The feelings and emotions that may occur as a reaction to a traumatic event include guilt, fear, feeling helpless, or powerless. The experience may have either short-term or long-term effects on a person’s well-being and can change an individual’s self-perception, self-esteem and self-efficacy. Having survived a traumatic event, people may doubt the ability of those around them to keep them safe, may lose trust in family and friends, and their faith in the world and their environment can also be eroded ((SAMHSA). (2014); National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Individuals with trauma may feel they are not worthy of love or protection.

Trauma before birth

It must be noted that trauma can occur even while a child is still pre-born; this is referred to as ‘In Utero’ trauma. Trauma in utero is often the result of chaotic or unpredictable lifestyle factors (ACT, 2019:1) which may involve the birth mother being involved in situations of domestic violence, experiencing a lack of support or antenatal care, or through taking substances that are harmful to both mother and fetus. Through being subject to these situations, raised levels of cortisol in the body can lead to changes in the child’s developing brain. Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is a common disorder that can result from the mother consuming alcohol during pregnancy; just one example of external events that impacts a child’s development. When trauma occurs in utero, the brain cannot develop in a healthy way, and this can lead to parts of the brain becoming oversensitive to stress which has an impact on the development of parts of the brain that control impulses and decision-making (ACT, 2019). Once the child is born, there are already behavioural difficulties resulting from the trauma in utero.

Supporting children with trauma

In order to support children who have suffered trauma, it is first important to have a rudimentary understanding of how trauma affects the developing child. Childhood trauma affects the reward, the memory and the threat systems. Children may be extremely sensitive to the behaviour and emotions of others, trying to pick up on small cues which may indicate that the adults around them are not happy. They may also have difficulty expressing their own emotions and internalise feelings of stress and anxiety.

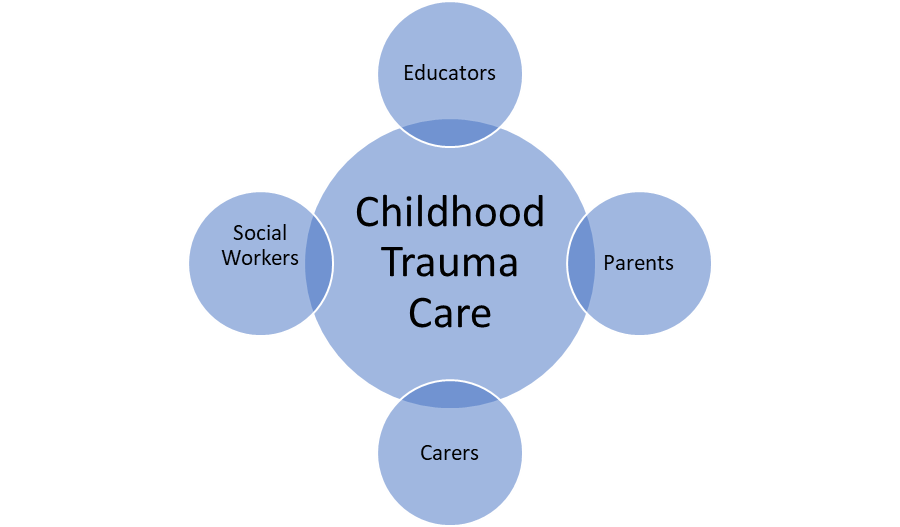

The matrix model of trauma care (shown in Figure 2 below) encompasses the impact educators, parents, carers and social workers can have on helping a child heal from trauma. These four groups have been chosen as the most influential groups to help have an impact on the prevention of early trauma, as well as having the ability to recognise the signs and intervene to help a child who has suffered trauma. The majority of children will have contact with at least one of these groups each day, therefore we believe trauma-informed practices should begin with these individuals in order to best optimise a child’s care.

Complex trauma occurs when more than one event has been experienced, or it has been a series of events (Hughes, 2016). Some examples of complex trauma include chronic abuse, or neglect, or observing violence; the child is being subject to experiences that they cannot process and do not have the understanding; let alone coping mechanisms for. Complex trauma can often have the most detrimental effects as it commonly occurs during these critical stages of brain development in early childhood before a child has learned how to cope with stress, and this can lead to both behavioural and academic difficulties as the child grows (NCSSLE, 2021).

In more recent years, many mental health specialists use the term ‘developmental trauma’ to refer to intra-familial trauma (Hughes, 2016) where children have, for example, been abused or neglected by their primary caregivers. Developmental trauma can perhaps be the most serious trauma of all, as it can cause a child to have negative thoughts about themselves and their future as well as the expectation of further trauma or the absence of care and protection from others (Gregorowski and Seedat, 2013). If a child is brought up in a hostile environment, the child’s threat system will adapt to this and they may become hypervigilant and highly alert to the threat around them (UK Trauma Council, 2020). This hypervigilance to threat can later lead to issues with behaviour and social functioning. For example, a child who has suffered trauma may react badly to a playful nudge, this may set off their hypervigilance to threat and they may respond through fighting. This will then lead to further issues for the child if educational practitioners are not trauma-informed and respond appropriately.

Symptoms and behaviours of trauma

‘Traumatic experiences come in many forms, ranging from one-time events to experiences that are chronic or even generational’ (NCSSLE, 2021).

One of the challenges for educators when recognising signs of trauma is the fact that children may not always express their distress and the way they are feeling, in a way that is easily understood. Children may try to mask their pain with behaviours that are aggressive or off-putting (Miller, 2021). Every child will react differently to trauma suffered, some children may not make the link between these behaviours and the trauma they have experienced.

The following signs of traumatic stress in children are suggested by The Royal College of Psychiatrists (2021):

– Appearing more fearful and clingier – demonstrating anxiety around being separated from parents

– Showing a preoccupation with thinking about the event

– Being unable to concentrate

– Being irritable and disobedient

– Suffering physical symptoms such as headaches and stomach aches

Further symptoms of trauma are also outlined by Nealy-Oprah and Scruggs-Hussein in 2020:

– Intrusive Memories

– Emotional Overwhelm

– Shame, Self – Hatred

– Eating Disorders

– Self-Destructive Behaviours

– Little or No Memories

– Hypervigilance

– Irritability

– Depression

– Dissociation

– Loss Of Interest

– Decreased Concentration

– Hopelessness

It is important for these symptoms to be recognised as possible indicators of trauma so that the appropriate support can be given. For example, if a child is becoming increasingly disruptive in class and showing a lack of interest, educators should first explore what could be causing this behaviour. That’s not to say every child appearing to misbehave or struggle in school has suffered trauma, however having a trauma-informed awareness allows there to be systems in place to support each child to help overcome these behaviours, as opposed to following disciplinary procedures straight away. This approach will also provide earlier opportunities to address other issues children may be experiencing. There should therefore be a focus on acknowledging the difficult emotions a child is feeling, demonstrating to the child that this emotion is seen and understood, whilst exploring what can be done to support them and enable them to express their strong feelings in a different way.

Building attachments: supporting children who have experienced trauma

Trauma can sometimes present itself through attachment difficulties. Any individual who has experienced the event of a major loss or a significant change during their life, such as parents separating and thus the child losing part of their familial network, or anyone who feels that their care was not consistent or that they were neglected or abused by those who should have protected them, may find it harder to build attachments (NCSSLE, 2021).

Verrier (2009) warns that for children who go into care as a ‘looked after child’/’child looked after’ (LAC/CLA), or that are adopted, the very act of removal from the birth mother, even if as a very young baby, causes trauma. It is important to remember, however, that not all looked after children have attachment difficulties and not all children with attachment difficulties are looked after by a local authority.

Children who have attachment difficulties can experiences barriers to learning through the inability to form meaningful relationships with staff and supporting adults (Wall, 2021). Children who have suffered trauma may not feel supported by the adults around them in their personal life, it is therefore important for schools to be a safe place for children, physically, emotionally, and socially. Children who have suffered trauma may initially find it hard to trust adults and to know how to ask for help. It is therefore important for there to be a focus of building trusting relationships within schools.

– Known members of staff children feel they can safely talk to

– Calming techniques taught in school such as mindfulness, positive self-talk, positive imagery

– Create opportunities for children to talk – for example, regular meetings with a specified member of staff

– Present school as a safe, neutral space for children

– Focus on positive reinforcement

– Validate a child’s feelings

Creating a trauma-sensitive school

The authors of this paper advise those in education to explore creating a ‘trauma-sensistive’ environment, which comes from the development of a safe and supportive space for children with trauma. Six trauma-sensitive practices as promoted by the NCSSLE (2021) are show in Box A below:

| Supporting staff development on the subject of trauma |

| Creating a safe and inclusive environment |

| Assess children’s needs and provide relevant support |

| Develop social and emotional skills |

| Work in partnership with students and families |

| Adapt schools policies and procedures |

Previous research has also suggested six ways in which a school can become trauma-informed (Jacobson, M. 2020).

– Having an understanding of the impact of trauma

– Providing support for children to feel safe

– Holistically addressing a student’s needs

– Connecting students to the school community

– Embracing teamwork

– Anticipating and adapting to the needs of students

What can social workers and care givers do to help?

What can social workers do to help? Initial help can be offered before a child is born. Professionals must encourage and support expectant mothers to find support in ending the misuse of alcohol and dangerous substances, both of which affect the unborn baby. There is a stigma attached to seeking help while pregnant (ACT, 2019) which may make mothers hesitate, but with the guidance and signposting of social workers this can help to reduce trauma at the start. For those expectant mothers who may be living in situations of domestic violence, social workers must monitor the situation and continually assess risks (ACT, 2019).

What can carer givers do to help? If a child is taken into care, the foster carer has an essential role in involving the child in play and helping the child to develop through meaningful interactions. The foster carer can help show the child how to turn take, share, and enjoy social experiences, whilst building trust and self-worth (ACT, 2019). Stories and puppets can help offer opportunities to talk about feelings. Physical activities such as bouncing on a trampoline, trampette, or swinging can help a child to feel regulated. Carers can teach ‘stimming’ activities, which refers to repetitive movements or noises and helps a child to manage their feelings and also keep calm in unfamiliar or strange places; important when trauma means a child may feel on edge and reactive (Raising Children, 2020). Care givers must be vigilant when identifying a child’s cues, both verbal and non-verbal, and consider any triggers that have led to flight, flight or freeze behaviours.

Carer givers must be a strong role models for emotional regulation; ‘emotional regulation or self regulation is the ability to monitor and modulate which emotions one has, when you have them, and how you experience and express them’ (Li, 2021: 1). Importantly, this does not mean that care givers should only show positive emotions; on the contrary, it is important to accept that conflicts, sadness and anger are all valid, and to model to children how to manage these situations and problems in a healthy way. For a child that has experienced trauma, it is vital that the home is seen as a safe space. The home environment must offer both physical safety and emotional safety. Over time this will help the child experience the world as a safe place and shift their internal working model of themselves as lovable and worthwhile (ACT, 2019).

For all adults who work with children that have experienced trauma, the key is to work on creating that positive and trusting relationship, where attachment difficulties may one day be overcome and potential to succeed can be unlocked (Wall, 2021). Always speak with a calm and even tone, and demonstrate compassion and curiosity about the child’s behaviour, needs, interests and experiences (ACT, 2019)

Charities, useful resources and further support

Two key websites that the authors recommend for further reading and resources are the UK Trauma Council, and Beacon House:

UK Trauma Council: Creating a world that nurtures and protects children and young people following trauma Our mission is to radically improve the help children and young people receive across the UK following traumatic events and experiences.

Beacon House: Therapeutic Services and Trauma Team: Beacon House is passionate about developing freely available resources so that knowledge about the repair of trauma and adversity is in the hands of those who need it.

Conclusion

To conclude, this article has presented ways in which parents, caregivers, educators and social workers, can better support children who have suffered trauma. Trauma can have a long-lasting, if not life-long impact, on an individual’s life, and it is essential that agencies work together to raise trauma-awareness and offer trauma-sensitive practices. This article is just an introduction to understanding trauma and its effects; research in this area is ever evolving as our integrative understanding develops and improves. It truly takes a village to provide this trauma-informed network and it is important that all adults work in partnership to help each child feel loved, safe and worthy.

References

ACT (2019) The in utero experience: trauma before birth. Available at https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/1549761/The-in-utero-experience-web.pdf [Accessed 10th November 2021]

Cole, S., Greenwald O’Brien, J., Gadd, M. G., Ristuccia, J., Wallace, D. L., Gregory, M.(2005). Helping traumatized children learn: A report and policy agenda. Massachusetts Advocates for Children. Accessed November 17th 2021 from: https://traumasensitiveschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Helping-Traumatized-Children-Learn.pdf

Davis, E.P., Glynn, L.M., Waffarn, F. & Sandman, C.A. (2011). ‘Prenatal Maternal Stress Programs Infant Stress Regulation’. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52(2), 119–129.

Gerin, M. Hanson, E. Viding, E & McCrory, E. (2019). A review of childhood maltreatment, latent vulnerability and the brain: implications for clinical practice and prevention. Adoption & Fostering. Volume 43, pp: 310-328.

Glasofer, D. R. (2021) DSM-5 Criteria for generalised anxiety disorder available at https://www.verywellmind.com/dsm-5-criteria-for-generalized-anxiety-disorder-1393147 [Accessed 13/5/2021]

Gregorowski, C and Seedat, C. (2013). Addressing childhood trauma in a developmental context. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Volume 25(2): 105–118. DOI: 10.2989/17280583.2013.795154

Huestis, M. & Choo, R. (2002). ‘Drug abuse’s smallest victims: in utero drug exposure’. Forensic Science International, 128, 20-30. https://kundoc.com/ pdf-drug-abuses-smallest-victims-in-utero-drug-exposure-.html

Hughes, D. 2016. Parenting a child who has experienced trauma. London: CoramBAAF.

Jacobson, M.R. (2021) An exploratory analysis of the necessity and utility of trauma-informed practices in education, Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth,65:2, 124-134, DOI: 10.1080/1045988X.2020.1848776

Kataoka, S. Vona, P. Acuna, A. Jaycox, L. Escudero, P. Rojas, C. Ramirez, E. Langley, A. & Stein, B. (2018). Applying a Trauma Informed School Systems Approach: Examples from School Community-Academic Partnerships. Ethnicity And Disease. Volume 28 (2). PP-417-426.

Li, P. (2021) Emotional Regulation in Children | A Complete Guide. Available at https://www.parentingforbrain.com/self-regulation-toddler-temper-tantrums/ [Accessed 20th November 2021]

Lindemann, E. 1944. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. AM J Psychiatry 101: 144-148

Miller, C. (2021). How trauma affects kids in school. Child Mind Institute. Accessed November 17th from: https://childmind.org/article/how-trauma-affects-kids-school/

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Understanding child traumatic stress. Retrieved from http://www.nctsnet.org/sites/default/files/assets/pdfs/understanding_child_traumatic_stress_brochure_9-29-05.pdf [Accessed 1st September 2021]

NCSSLE (2021) Understanding Trauma and Its Impact. Available at https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/understanding-trauma-and-its-impact [Accessed 10th November 2021]

Nealy-Oparah, S. and Scruggs-Hussein, T. (2020). Trauma-informed leadership in schools: From the Inside-Out. Accessed November 17th 2021 from: https://resilientfutures.us/wpcontent/uploads/2020/02/TraumaInformedLeadershipinSchools-1.pdf

Pataky, M.G. , Johanna Creswell Báez & Kristen J Renshaw (2019) Making schools trauma informed: using the ACE study and implementation science to screen for trauma, Social Work in Mental Health, 17:6, 639-661, DOI: 10.1080/15332985.2019.1625476

Raising Children (2020) Stimming: autistic children and teenagers. Available at https://raisingchildren.net.au/autism/behaviour/common-concerns/stimming-asd [Accessed 15th November 2021]

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services (Treatment Improvement Protocol [TIP] Series 57, HHS Publication No. [SMA] 14-4816). Rockville, MD: Author.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2021). Traumatic stress in children: for parents and carers. Accessed November 16th 2021 from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/parents-and-young-people/information-for-parents-and-carers/traumatic-stress-in-children-for-parents-and-carers

UK Trauma Council. (2020). The Guidebook To Childhood Trauma And The Brain. Accessed November 15th 2021 from: https://uktraumacouncil.link/documents/CHILDHOOD-TRAUMA-AND-THE-BRAIN-SinglePages.pdf.

Van der Kolk, B.A., 2003. Psychological trauma. American Psychiatric Pub. Available at https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Dp2gi8t8zLEC&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=what+is+trauma&ots=l1HqXtRZbl&sig=4dYJG-sPhS_f5sRHspaLU670hTI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=what%20is%20trauma&f=false

Verrier, N.N. (2009) The Primal Wound: Understanding the adopted child. London: CoramBAAF.

Wall,S. (2021) ‘A little whisper in the ear’: how developing relationships between pupils with attachment difficulties and key adults can improve the former’s social, emotional and behavioural skills and support inclusion, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, DOI: 10.1080/13632752.2021.1979322 Available at https://content.talisaspire.com/anglia/bundles/616ec64949e61b326d2edd14

Co-author: Amber Bale, Master of Psychology Student